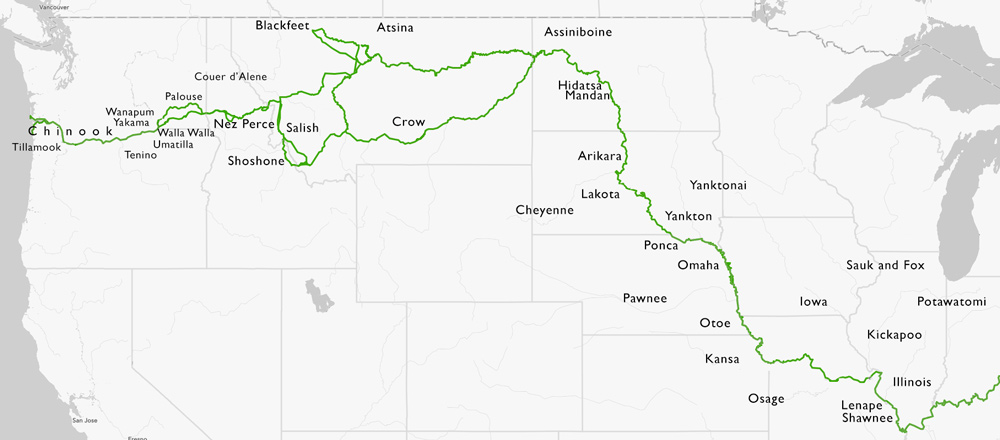

“Certainly the Lewis and Clark expedition benefited greatly from the Indians’ knowledge and support. Maps, route information, food, horses, open-handed friendship—all gave the Corps of Discovery the edge that spelled the difference between success and failure.”

Native American Nations Encountered

Northeast

Prairie Plains

High Plains

Southwest

Plateau

Related Ethnography

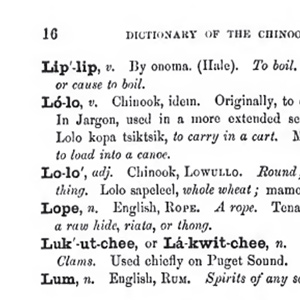

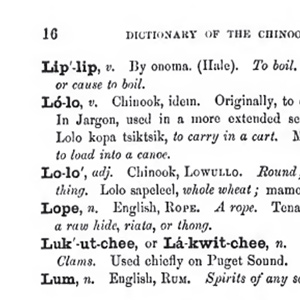

Lewis and Clark appear to have been unaware of the existence of Chinook Trade Jargon. Never-the-less, some of the words they encountered would be later documented as part of the jargon.

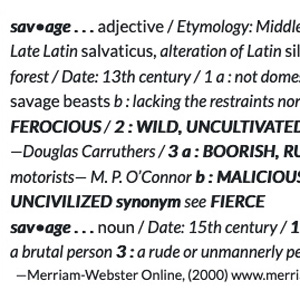

The word has two faces, one benign, the other brutish. The first springs from its etymological history, and represents the face of pure innocence. On the darker side, it is closer to the Latin cognate, saevus, meaning brutal, cruel, barbarous, violent and severe.

Indian Gifts

Almost one-third of the $2,160 Lewis spent on purchases by Israel Whelan went for Indian presents, not only to supply some of the Indians’ anticipated wants but also to showcase some of the more attractive goods they might learn to want.

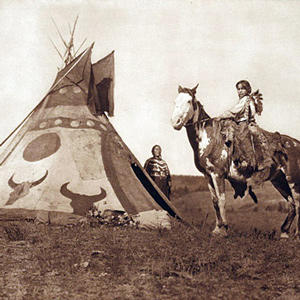

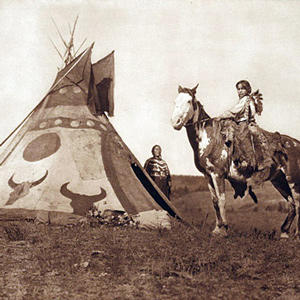

Indian Horses in the PNW

by Barbara Fifer

One of the reasons Clark had so much difficulty in purchasing horses at The Dalles in the spring of 1806 is that he was at the very northwestern edge of their dispersal across North America.

Next to grizzly bears and Mother Nature, the most feared enemy of American fur trappers traveling along the upper Missouri River were the Niitsítapi or Blackfeet, the “Original People” or “Prairie People.” Was that Lewis’s fault?

Both of the captains referred to Charbonneau’s young wife as a squaw, usually spelling it with a post-vocalic /r/—”Squar.” In the 1980s a nationwide movement arose to extirpate squaw from general use, because of its worst connotations.

Rush’s Questions for Indians

Vices, morals, and religion

Benjamin Rush provided Lewis this list of questions about Indian medicine, vices, and religion.

The Lewis and Clark’s bear claw necklace, recently ‘rediscovered’, is described and analyzed and suggests some of the many meanings and provocations related to it.

Indian Maps

by John Logan Allen

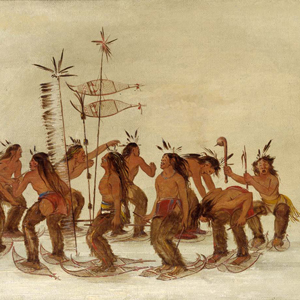

The native peoples encountered by Lewis and Clark differed from non-Indians in their manner of linking space and time, distance and direction. The reasons were primarily the result of the contrasting needs of the hunter-gatherer and subsistence farmer versus those of the commercial farmer, townsman, or tradesman.

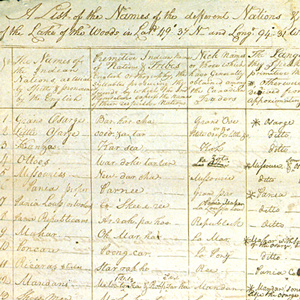

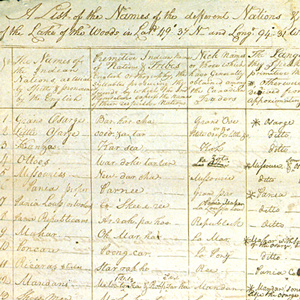

The expedition had one major outcome that was made available to the public well before the expedition was over, the “Estimate of the Eastern Indians,” which Lewis and Clark sent back on the barge in April 1805.

Beginning with the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851, the U.S. government set the vast area north of the Missouri (approximately 20 million acres) aside as the “Blackfeet Hunting Ground” for the Blackfeet and other tribes—Cree, Assiniboine, Gros Ventre, and Sioux.

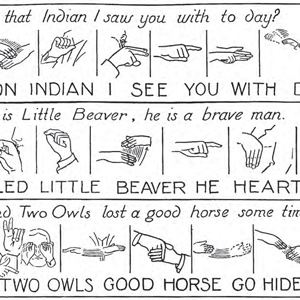

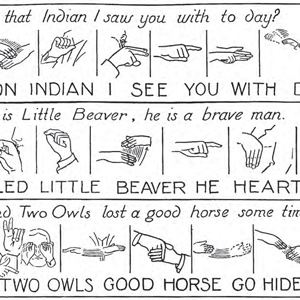

“our guide could not speake the language of these people but soon engaged them in conversation by signs or jesticulation, the common language of all the Aborigines of North America.” Lewis exaggerated the universality of sign language, which was mainly employed by tribes of the Great Plains.

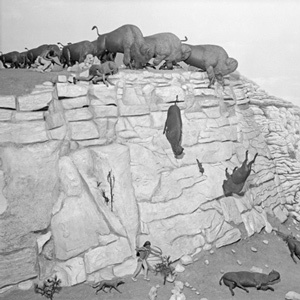

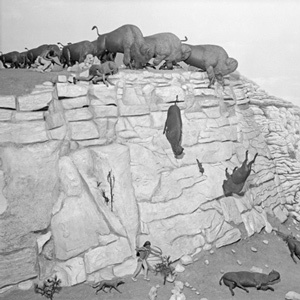

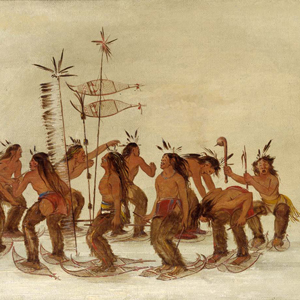

Early American Hunting

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Governor William Bradford of the Massachusetts Bay Colony hired the local Indians to hunt for the colony. Early Americans later learned several hunting methods from Indians such as relaying, driving, and still hunting.

Indigenous Agriculture

Archaeological evidence indicates that deliberate burning of forests and fields has been occurring on the North American continent for at least the past 10,000 to 20,000 years. In 1603, Samuel de Champlain took Jerusalem Artichokes found in Indian gardens back to France where it soon became a staple food there. The cultivation and storage of important food plants had long been practiced before Euro-Americans came to teach the Native Americans about agriculture.

Lewis and Clark as Ethnographers

by James P. Ronda

As ethnographers, the captains provided “names of the nations & their numbers” and recorded the strange cultures they encountered. Their work as ethnographers is examined here by James Ronda.

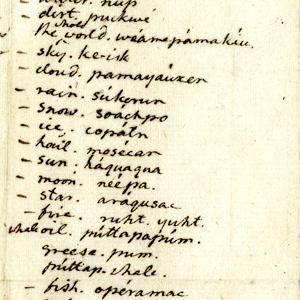

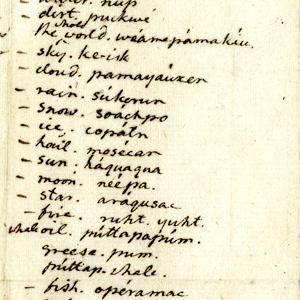

The Indian Vocabularies

by Bob Saindon

Due to the many unfortunate events which followed Lewis’s death, in 1809, the Indian vocabularies the captains had carefully collected are now lost, and were never made available to the public.

Bostonian George Ticknor catalogued the “strange furniture” of the four walls of the room after his visit in 1815, listing heads and horns, “curiosities which Lewis and Clark found on their wild and perilous expedition,” mastodon bones, and the two Native American painted hides.

The comments made by Ordway and Gass about Frazer selling his razor for two Spanish dollars can tell us much about the ethno-history of the Lewis and Clark Expedition and the native peoples of the Plateau.

Nations by Language Family

Siouan Peoples

by Kristopher K. Townsend

On 31 August 1804, Clark, frustrated in his attempt to draw a clear picture of the Sioux, summarized what he did know. “This Nation is Divided into 20 Tribes possessing Seperate interests . . . .”

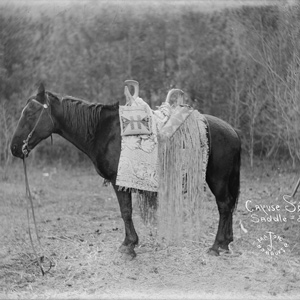

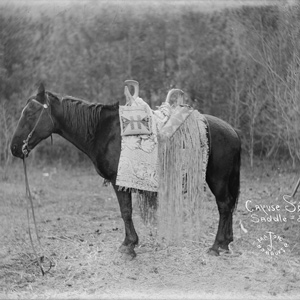

The Cayuses

by Kristopher K. Townsend

Clark’s name for the Cayuse, the Ye-E-al-po Nation, may have been his phonetic spelling of the Nez Perce name for them—Waiilatpu. The people are noted for their namesake horses and the 1847 murders at the Whitman Mission.

The Lemhi Shoshones

by Stephen E. Ambrose

The Lemhi Shoshones were the first Indians they had seen since leaving the Hidatsas and Mandans. In describing them, Lewis was breaking entirely new scientific ground. His account is therefore invaluable as the first description ever of a Rocky Mountain tribe, in an almost pre-contact stage.

Two widely separated branches of Salishan languages developed prior to 1800, Coastal and Interior. Lewis and Clark encountered several nations from both of these branches.

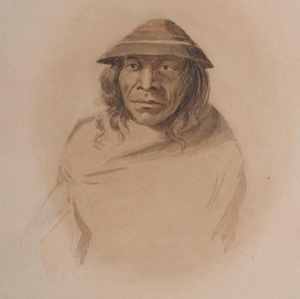

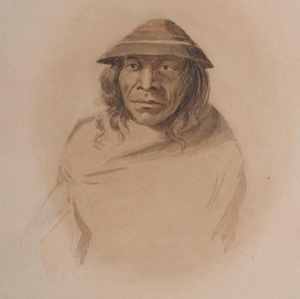

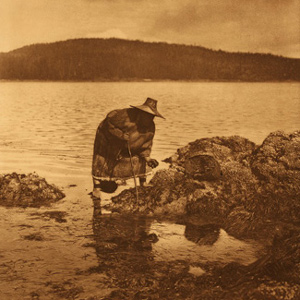

Chinookan Peoples

by Barbara Fifer

The Lewis and Clark Expedition first encountered Chinookan-speaking people at the Dalles of the Columbia River. Upper and Lower Chinookan tribes were in contact as the expedition traveled to the river’s mouth, wintered at Fort Clatsop, and returned home in spring 1806.

Algonquian Peoples

The Lewis and Clark Expedition encountered Algonquian-speaking on the Ohio, the Mississippi River, throughout the plains, and as far as the Two Medicine River in Northwestern Montana.

Sahaptin Peoples

by Barbara Fifer

From The Dalles, Sahaptian (also Shahaptian) languages extended eastward to the Rocky Mountains. Speakers of these languages met by the Corps included the Walla Wallas, Klickitats, Teninos, Umatillas, Yakamas, Wanapums, and Nez Perces.

Caddoan Peoples

The Caddoan languages are Caddo, Kitsai, Wichita, Pawnee, and Arikara. Just prior to the Lewis and Clark Expedition, Caddoan-speaking nations had inhabited the plains from southeastern Texas to North Dakota.

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.